Home / This Is Why Students Use Flashcards

Case Studies of Successful O-Chem Students

This Is Why Students Use Flashcards

Last updated: January 23rd, 2024 |

A long but interesting letter from a reader who I’ll call “Annie” on how preparing for an exam the “right way” (learning the mechanisms for every reaction) as opposed to the ‘wrong way’ (flashcards) actually led to worse results (emphases are mine).

My entire life I’ve been hearing people say variations of “In first semester ochem you’re going to come to a fork in the road where some people will choose to memorize a whole bunch of stuff but other people will have no need to memorize because they will actually deep-down understand it. Make sure you’re in the second group because, man, [insert a zillion reasons].”

I took that to heart. I’m taking a compressed orgo course this fall; we just took our second exam last Friday, it was the first that had any mechanisms. Determined to not be one of these so-called memorizers, I spent the whole weekend learning maybe thirty mechanisms from the ground-up, going through them again and again until all the arrow pushing was natural and understandable and routine. Of course some of these (say…ozonolysis) were pretty involved and kind of a pain and every second I sat in my kitchen learning it probably cost me three or four seconds of overall life expectancy.

But I’ll get to the point, and spoiler alert, it involves whining.

The actual test was unexpected. A typical mechanism question was “ok, here’s a goofy alkene: What would the product be if we applied these SIX reagents to it in this order?” And then the six reagents would just be stacked top-to-bottom on top of the central arrow.

I didn’t know there were going to be questions like that, and I”m only mentioning this because I suddenly felt like I was at a sort of a weird disadvantage. The way I had learned mechanisms, each one of those exam problems was necessarily a fifty-step deathmarch taking fifteen minutes each to solve, check, and recheck.

But for everyone who had just memorized thirty quick flashcards with only starting molecule / reagents / product, then those questions were thirty-second plug-and-chug victory laps.

While this email probably looks like I am just venting about how I feel misled or duped or that my friends in the class took the easy way out, that’s really not it at all, because on the contrary, I feel like they were all very smart about it, and that I completely lost the plot, because sitting here now, my ability to walk stepwise through the many mysteries of hydroboration seems not only sort of useless, but it legitimately hurt me on that exam: that section took me an hour and would have been easy to flub a methyl here or there, while meanwhile the whole flashcard army was getting all the points, and an extra hour on the test, and an extra week spent running barefoot on the beach towards a test which I assume for them was at worst good and at best an unequivocal markovnikovian triumph of drawing tiny tiny lines.

What happened here?

Let’s break down what happened.

- The student was given advice that memorizing reactions and mechanisms would have dire consequences.

- In preparation, she spent a ton of time learning all the mechanisms in detail, and didn’t rote-memorize the pattern of products formed in each reaction.

- When she took the exam, she felt she was at a disadvantage relative to her “flashcard army” peers, because she never learned to quickly determine what the product of a given reaction was without going through its mechanism.

- She feels cheated because she feels she studied the “right way” – spending a great deal of time learning arrow-pushing mechanisms – but was penalized for it, in that In the future, she’ll likely adopt the “flashcard” strategy that did well for her peers.

Essentially, this is a complaint about what was tested on the exam. Had her instructor tested people on their knowledge of mechanisms, she would have aced it. But instead, the exam tested the products of reactions – and in this respect, she was at a disadvantage, even through preparing for an exam that tests in this manner would have required less time to study for.

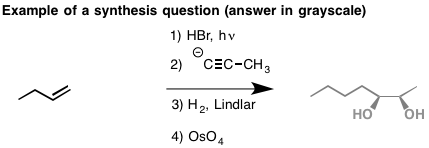

Explaining why it takes more time requires adding a figure. Let me show you an example of the type of question Annie is referring to:

Here, we’re given a starting alkene, and then are asked to apply the results of 4 reactions to get a final product (which I’ve shown in grayscale – obviously you wouldn’t see this on the exam).

The “quick” way to answer these questions is to know the pattern of what bonds are formed and broken in each reaction. This is something that is easily drilled by making flashcards.

[For instance, 1) HBr, H2O2 and hν is addition of HBr to the alkene under free-radical conditions. This breaks the C-C pi bond, and forms C-H and C-Br in a way that Br adds to the least substituted carbon [anti-Markovnikov addition]. This produces a new alkyl halide, and step 2) is addition of an acetylide, which does an SN2 reaction, forming C-C and breaking C-Br. Step 3) is Lindlar partial hydrogenation of an alkyne, which breaks the alkyne C-C pi bond, forming two adjacent C-H bonds in a way to make a cis alkene – and finally, step 4) is dihydroxylation of an alkene with OsO4 to give a syn diol: break C-C pi, and form two adjacent C-OH bonds on the same face of the alkene].

Annie’s way, which is much slower, requires drawing out the mechanism for each reaction in order to obtain the final product. That certainly shows deeper knowledge of each reaction, but it’s extremely time consuming.

What Instructors Test For Ultimately Determines How Students Study

Had the instructor had instead tested on the mechanisms of various reactions, it could very well have been a member of the “flashcard army” who emailed me with their “I studied badly” story, resolving to tear up their flashcards and instead learning the arrow pushing for each reaction in detail for the next exam. But how often does that happen?

Recently I looked at a few dozen exams (midterms and finals) in first semester organic chemistry, focusing particularly on alkenes. I found 334 exam problems. Of those 334, here’s how they broke down.

Predict the products: 201

Draw reagents/intermediate: 49

Give starting material: 11

Provide mechanism: 50

Other: 23

Of those 334 questions, 261 (78%) were some variation of a reaction that could be easily studied with a standard flashcard design (blanks for SM, reagent, and product). Only 50 (15%) concerned a mechanism. Now take that with a lot of salt, because mechanism questions are usually worth more points, and this was a relatively small sample of exams, as well as being just one section out of many in organic chemistry… but you get the idea. Students use flashcards because many instructors test their students in a way that rewards this method.

“Shallow” Preparation Takes Less Time Than “Deep” Preparation. So Most Students Should Start There.

Hence, I tell most students that it’s smart to “start shallow, then then go deep”. By that, I mean, focus on answering the “what” questions before you get to answering “how” or “why”. My classic “what” question, which will go on my tombstone, is “What Bonds Form, What Bonds Break?”. [I covered Shallow vs. Deep in my last post on “Learning Reactions: A Checklist“]. The factual questions take less time to learn than the tough work of learning to apply concepts (a skill which often takes a lot of practice problems to sharpen).

There are exceptions – I’ve tutored some of Maitland Jones’ students at NYU, for instance, and they learn pretty quickly that flashcards are not nearly as helpful as working a lot of different problems. And there are many other instructors out there who love to make their students think (University of Michigan, George Mason U, and a lot of schools in New York State, to start). But these are not the majority.

One last word which I hope students like Annie will take to heart. The weakness of the flashcard army is that they start to think that learning the facts of reactions is all there is. While it’s absolutely necessary to learn the facts, it’s even more important not to stop there, because many final exams (including the standardized ACS exams) can be very conceptual. Start shallow… but then go deep.

00 General Chemistry Review

01 Bonding, Structure, and Resonance

- How Do We Know Methane (CH4) Is Tetrahedral?

- Hybrid Orbitals and Hybridization

- How To Determine Hybridization: A Shortcut

- Orbital Hybridization And Bond Strengths

- Sigma bonds come in six varieties: Pi bonds come in one

- A Key Skill: How to Calculate Formal Charge

- The Four Intermolecular Forces and How They Affect Boiling Points

- 3 Trends That Affect Boiling Points

- How To Use Electronegativity To Determine Electron Density (and why NOT to trust formal charge)

- Introduction to Resonance

- How To Use Curved Arrows To Interchange Resonance Forms

- Evaluating Resonance Forms (1) - The Rule of Least Charges

- How To Find The Best Resonance Structure By Applying Electronegativity

- Evaluating Resonance Structures With Negative Charges

- Evaluating Resonance Structures With Positive Charge

- Exploring Resonance: Pi-Donation

- Exploring Resonance: Pi-acceptors

- In Summary: Evaluating Resonance Structures

- Drawing Resonance Structures: 3 Common Mistakes To Avoid

- How to apply electronegativity and resonance to understand reactivity

- Bond Hybridization Practice

- Structure and Bonding Practice Quizzes

- Resonance Structures Practice

02 Acid Base Reactions

- Introduction to Acid-Base Reactions

- Acid Base Reactions In Organic Chemistry

- The Stronger The Acid, The Weaker The Conjugate Base

- Walkthrough of Acid-Base Reactions (3) - Acidity Trends

- Five Key Factors That Influence Acidity

- Acid-Base Reactions: Introducing Ka and pKa

- How to Use a pKa Table

- The pKa Table Is Your Friend

- A Handy Rule of Thumb for Acid-Base Reactions

- Acid Base Reactions Are Fast

- pKa Values Span 60 Orders Of Magnitude

- How Protonation and Deprotonation Affect Reactivity

- Acid Base Practice Problems

03 Alkanes and Nomenclature

- Meet the (Most Important) Functional Groups

- Condensed Formulas: Deciphering What the Brackets Mean

- Hidden Hydrogens, Hidden Lone Pairs, Hidden Counterions

- Don't Be Futyl, Learn The Butyls

- Primary, Secondary, Tertiary, Quaternary In Organic Chemistry

- Branching, and Its Affect On Melting and Boiling Points

- The Many, Many Ways of Drawing Butane

- Wedge And Dash Convention For Tetrahedral Carbon

- Common Mistakes in Organic Chemistry: Pentavalent Carbon

- Table of Functional Group Priorities for Nomenclature

- Summary Sheet - Alkane Nomenclature

- Organic Chemistry IUPAC Nomenclature Demystified With A Simple Puzzle Piece Approach

- Boiling Point Quizzes

- Organic Chemistry Nomenclature Quizzes

04 Conformations and Cycloalkanes

- Staggered vs Eclipsed Conformations of Ethane

- Conformational Isomers of Propane

- Newman Projection of Butane (and Gauche Conformation)

- Introduction to Cycloalkanes

- Geometric Isomers In Small Rings: Cis And Trans Cycloalkanes

- Calculation of Ring Strain In Cycloalkanes

- Cycloalkanes - Ring Strain In Cyclopropane And Cyclobutane

- Cyclohexane Conformations

- Cyclohexane Chair Conformation: An Aerial Tour

- How To Draw The Cyclohexane Chair Conformation

- The Cyclohexane Chair Flip

- The Cyclohexane Chair Flip - Energy Diagram

- Substituted Cyclohexanes - Axial vs Equatorial

- Ranking The Bulkiness Of Substituents On Cyclohexanes: "A-Values"

- Cyclohexane Chair Conformation Stability: Which One Is Lower Energy?

- Fused Rings - Cis-Decalin and Trans-Decalin

- Naming Bicyclic Compounds - Fused, Bridged, and Spiro

- Bredt's Rule (And Summary of Cycloalkanes)

- Newman Projection Practice

- Cycloalkanes Practice Problems

05 A Primer On Organic Reactions

- The Most Important Question To Ask When Learning a New Reaction

- Curved Arrows (for reactions)

- Nucleophiles and Electrophiles

- The Three Classes of Nucleophiles

- Nucleophilicity vs. Basicity

- What Makes A Good Nucleophile?

- What Makes A Good Leaving Group?

- 3 Factors That Stabilize Carbocations

- Equilibrium and Energy Relationships

- 7 Factors that stabilize negative charge in organic chemistry

- 7 Factors That Stabilize Positive Charge in Organic Chemistry

- What's a Transition State?

- Hammond's Postulate

- Learning Organic Chemistry Reactions: A Checklist (PDF)

- Introduction to Oxidative Cleavage Reactions

06 Free Radical Reactions

- Bond Dissociation Energies = Homolytic Cleavage

- Free Radical Reactions

- 3 Factors That Stabilize Free Radicals

- What Factors Destabilize Free Radicals?

- Bond Strengths And Radical Stability

- Free Radical Initiation: Why Is "Light" Or "Heat" Required?

- Initiation, Propagation, Termination

- Monochlorination Products Of Propane, Pentane, And Other Alkanes

- Selectivity In Free Radical Reactions

- Selectivity in Free Radical Reactions: Bromination vs. Chlorination

- Halogenation At Tiffany's

- Allylic Bromination

- Bonus Topic: Allylic Rearrangements

- In Summary: Free Radicals

- Synthesis (2) - Reactions of Alkanes

- Free Radicals Practice Quizzes

07 Stereochemistry and Chirality

- Types of Isomers: Constitutional Isomers, Stereoisomers, Enantiomers, and Diastereomers

- How To Draw The Enantiomer Of A Chiral Molecule

- How To Draw A Bond Rotation

- Introduction to Assigning (R) and (S): The Cahn-Ingold-Prelog Rules

- Assigning Cahn-Ingold-Prelog (CIP) Priorities (2) - The Method of Dots

- Enantiomers vs Diastereomers vs The Same? Two Methods For Solving Problems

- Assigning R/S To Newman Projections (And Converting Newman To Line Diagrams)

- How To Determine R and S Configurations On A Fischer Projection

- The Meso Trap

- Optical Rotation, Optical Activity, and Specific Rotation

- Optical Purity and Enantiomeric Excess

- What's a Racemic Mixture?

- Chiral Allenes And Chiral Axes

- Stereochemistry Practice Problems and Quizzes

08 Substitution Reactions

- Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions - Introduction

- Two Types of Nucleophilic Substitution Reactions

- The SN2 Mechanism

- Why the SN2 Reaction Is Powerful

- The SN1 Mechanism

- The Conjugate Acid Is A Better Leaving Group

- Comparing the SN1 and SN2 Reactions

- Polar Protic? Polar Aprotic? Nonpolar? All About Solvents

- Steric Hindrance is Like a Fat Goalie

- Common Blind Spot: Intramolecular Reactions

- Substitution Practice - SN1

- Substitution Practice - SN2

09 Elimination Reactions

- Elimination Reactions (1): Introduction And The Key Pattern

- Elimination Reactions (2): The Zaitsev Rule

- Elimination Reactions Are Favored By Heat

- Two Elimination Reaction Patterns

- The E1 Reaction

- The E2 Mechanism

- E1 vs E2: Comparing the E1 and E2 Reactions

- Antiperiplanar Relationships: The E2 Reaction and Cyclohexane Rings

- Bulky Bases in Elimination Reactions

- Comparing the E1 vs SN1 Reactions

- Elimination (E1) Reactions With Rearrangements

- E1cB - Elimination (Unimolecular) Conjugate Base

- Elimination (E1) Practice Problems And Solutions

- Elimination (E2) Practice Problems and Solutions

10 Rearrangements

11 SN1/SN2/E1/E2 Decision

- Identifying Where Substitution and Elimination Reactions Happen

- Deciding SN1/SN2/E1/E2 (1) - The Substrate

- Deciding SN1/SN2/E1/E2 (2) - The Nucleophile/Base

- SN1 vs E1 and SN2 vs E2 : The Temperature

- Deciding SN1/SN2/E1/E2 - The Solvent

- Wrapup: The Key Factors For Determining SN1/SN2/E1/E2

- Alkyl Halide Reaction Map And Summary

- SN1 SN2 E1 E2 Practice Problems

12 Alkene Reactions

- E and Z Notation For Alkenes (+ Cis/Trans)

- Alkene Stability

- Alkene Addition Reactions: "Regioselectivity" and "Stereoselectivity" (Syn/Anti)

- Stereoselective and Stereospecific Reactions

- Hydrohalogenation of Alkenes and Markovnikov's Rule

- Hydration of Alkenes With Aqueous Acid

- Rearrangements in Alkene Addition Reactions

- Halogenation of Alkenes and Halohydrin Formation

- Oxymercuration Demercuration of Alkenes

- Hydroboration Oxidation of Alkenes

- m-CPBA (meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid)

- OsO4 (Osmium Tetroxide) for Dihydroxylation of Alkenes

- Palladium on Carbon (Pd/C) for Catalytic Hydrogenation of Alkenes

- Cyclopropanation of Alkenes

- A Fourth Alkene Addition Pattern - Free Radical Addition

- Alkene Reactions: Ozonolysis

- Summary: Three Key Families Of Alkene Reaction Mechanisms

- Synthesis (4) - Alkene Reaction Map, Including Alkyl Halide Reactions

- Alkene Reactions Practice Problems

13 Alkyne Reactions

- Acetylides from Alkynes, And Substitution Reactions of Acetylides

- Partial Reduction of Alkynes With Lindlar's Catalyst

- Partial Reduction of Alkynes With Na/NH3 To Obtain Trans Alkenes

- Alkyne Hydroboration With "R2BH"

- Hydration and Oxymercuration of Alkynes

- Hydrohalogenation of Alkynes

- Alkyne Halogenation: Bromination, Chlorination, and Iodination of Alkynes

- Alkyne Reactions - The "Concerted" Pathway

- Alkenes To Alkynes Via Halogenation And Elimination Reactions

- Alkynes Are A Blank Canvas

- Synthesis (5) - Reactions of Alkynes

- Alkyne Reactions Practice Problems With Answers

14 Alcohols, Epoxides and Ethers

- Alcohols - Nomenclature and Properties

- Alcohols Can Act As Acids Or Bases (And Why It Matters)

- Alcohols - Acidity and Basicity

- The Williamson Ether Synthesis

- Ethers From Alkenes, Tertiary Alkyl Halides and Alkoxymercuration

- Alcohols To Ethers via Acid Catalysis

- Cleavage Of Ethers With Acid

- Epoxides - The Outlier Of The Ether Family

- Opening of Epoxides With Acid

- Epoxide Ring Opening With Base

- Making Alkyl Halides From Alcohols

- Tosylates And Mesylates

- PBr3 and SOCl2

- Elimination Reactions of Alcohols

- Elimination of Alcohols To Alkenes With POCl3

- Alcohol Oxidation: "Strong" and "Weak" Oxidants

- Demystifying The Mechanisms of Alcohol Oxidations

- Protecting Groups For Alcohols

- Thiols And Thioethers

- Calculating the oxidation state of a carbon

- Oxidation and Reduction in Organic Chemistry

- Oxidation Ladders

- SOCl2 Mechanism For Alcohols To Alkyl Halides: SN2 versus SNi

- Alcohol Reactions Roadmap (PDF)

- Alcohol Reaction Practice Problems

- Epoxide Reaction Quizzes

- Oxidation and Reduction Practice Quizzes

15 Organometallics

- What's An Organometallic?

- Formation of Grignard and Organolithium Reagents

- Organometallics Are Strong Bases

- Reactions of Grignard Reagents

- Protecting Groups In Grignard Reactions

- Synthesis Problems Involving Grignard Reagents

- Grignard Reactions And Synthesis (2)

- Organocuprates (Gilman Reagents): How They're Made

- Gilman Reagents (Organocuprates): What They're Used For

- The Heck, Suzuki, and Olefin Metathesis Reactions (And Why They Don't Belong In Most Introductory Organic Chemistry Courses)

- Reaction Map: Reactions of Organometallics

- Grignard Practice Problems

16 Spectroscopy

- Degrees of Unsaturation (or IHD, Index of Hydrogen Deficiency)

- Conjugation And Color (+ How Bleach Works)

- Introduction To UV-Vis Spectroscopy

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Absorbance of Carbonyls

- UV-Vis Spectroscopy: Practice Questions

- Bond Vibrations, Infrared Spectroscopy, and the "Ball and Spring" Model

- Infrared Spectroscopy: A Quick Primer On Interpreting Spectra

- IR Spectroscopy: 4 Practice Problems

- 1H NMR: How Many Signals?

- Homotopic, Enantiotopic, Diastereotopic

- Diastereotopic Protons in 1H NMR Spectroscopy: Examples

- 13-C NMR - How Many Signals

- Liquid Gold: Pheromones In Doe Urine

- Natural Product Isolation (1) - Extraction

- Natural Product Isolation (2) - Purification Techniques, An Overview

- Structure Determination Case Study: Deer Tarsal Gland Pheromone

17 Dienes and MO Theory

- What To Expect In Organic Chemistry 2

- Are these molecules conjugated?

- Conjugation And Resonance In Organic Chemistry

- Bonding And Antibonding Pi Orbitals

- Molecular Orbitals of The Allyl Cation, Allyl Radical, and Allyl Anion

- Pi Molecular Orbitals of Butadiene

- Reactions of Dienes: 1,2 and 1,4 Addition

- Thermodynamic and Kinetic Products

- More On 1,2 and 1,4 Additions To Dienes

- s-cis and s-trans

- The Diels-Alder Reaction

- Cyclic Dienes and Dienophiles in the Diels-Alder Reaction

- Stereochemistry of the Diels-Alder Reaction

- Exo vs Endo Products In The Diels Alder: How To Tell Them Apart

- HOMO and LUMO In the Diels Alder Reaction

- Why Are Endo vs Exo Products Favored in the Diels-Alder Reaction?

- Diels-Alder Reaction: Kinetic and Thermodynamic Control

- The Retro Diels-Alder Reaction

- The Intramolecular Diels Alder Reaction

- Regiochemistry In The Diels-Alder Reaction

- The Cope and Claisen Rearrangements

- Electrocyclic Reactions

- Electrocyclic Ring Opening And Closure (2) - Six (or Eight) Pi Electrons

- Diels Alder Practice Problems

- Molecular Orbital Theory Practice

18 Aromaticity

- Introduction To Aromaticity

- Rules For Aromaticity

- Huckel's Rule: What Does 4n+2 Mean?

- Aromatic, Non-Aromatic, or Antiaromatic? Some Practice Problems

- Antiaromatic Compounds and Antiaromaticity

- The Pi Molecular Orbitals of Benzene

- The Pi Molecular Orbitals of Cyclobutadiene

- Frost Circles

- Aromaticity Practice Quizzes

19 Reactions of Aromatic Molecules

- Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution: Introduction

- Activating and Deactivating Groups In Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution

- Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution - The Mechanism

- Ortho-, Para- and Meta- Directors in Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution

- Understanding Ortho, Para, and Meta Directors

- Why are halogens ortho- para- directors?

- Disubstituted Benzenes: The Strongest Electron-Donor "Wins"

- Electrophilic Aromatic Substitutions (1) - Halogenation of Benzene

- Electrophilic Aromatic Substitutions (2) - Nitration and Sulfonation

- EAS Reactions (3) - Friedel-Crafts Acylation and Friedel-Crafts Alkylation

- Intramolecular Friedel-Crafts Reactions

- Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution (NAS)

- Nucleophilic Aromatic Substitution (2) - The Benzyne Mechanism

- Reactions on the "Benzylic" Carbon: Bromination And Oxidation

- The Wolff-Kishner, Clemmensen, And Other Carbonyl Reductions

- More Reactions on the Aromatic Sidechain: Reduction of Nitro Groups and the Baeyer Villiger

- Aromatic Synthesis (1) - "Order Of Operations"

- Synthesis of Benzene Derivatives (2) - Polarity Reversal

- Aromatic Synthesis (3) - Sulfonyl Blocking Groups

- Birch Reduction

- Synthesis (7): Reaction Map of Benzene and Related Aromatic Compounds

- Aromatic Reactions and Synthesis Practice

- Electrophilic Aromatic Substitution Practice Problems

20 Aldehydes and Ketones

- What's The Alpha Carbon In Carbonyl Compounds?

- Nucleophilic Addition To Carbonyls

- Aldehydes and Ketones: 14 Reactions With The Same Mechanism

- Sodium Borohydride (NaBH4) Reduction of Aldehydes and Ketones

- Grignard Reagents For Addition To Aldehydes and Ketones

- Wittig Reaction

- Hydrates, Hemiacetals, and Acetals

- Imines - Properties, Formation, Reactions, and Mechanisms

- All About Enamines

- Breaking Down Carbonyl Reaction Mechanisms: Reactions of Anionic Nucleophiles (Part 2)

- Aldehydes Ketones Reaction Practice

21 Carboxylic Acid Derivatives

- Nucleophilic Acyl Substitution (With Negatively Charged Nucleophiles)

- Addition-Elimination Mechanisms With Neutral Nucleophiles (Including Acid Catalysis)

- Basic Hydrolysis of Esters - Saponification

- Transesterification

- Proton Transfer

- Fischer Esterification - Carboxylic Acid to Ester Under Acidic Conditions

- Lithium Aluminum Hydride (LiAlH4) For Reduction of Carboxylic Acid Derivatives

- LiAlH[Ot-Bu]3 For The Reduction of Acid Halides To Aldehydes

- Di-isobutyl Aluminum Hydride (DIBAL) For The Partial Reduction of Esters and Nitriles

- Amide Hydrolysis

- Thionyl Chloride (SOCl2)

- Diazomethane (CH2N2)

- Carbonyl Chemistry: Learn Six Mechanisms For the Price Of One

- Making Music With Mechanisms (PADPED)

- Carboxylic Acid Derivatives Practice Questions

22 Enols and Enolates

- Keto-Enol Tautomerism

- Enolates - Formation, Stability, and Simple Reactions

- Kinetic Versus Thermodynamic Enolates

- Aldol Addition and Condensation Reactions

- Reactions of Enols - Acid-Catalyzed Aldol, Halogenation, and Mannich Reactions

- Claisen Condensation and Dieckmann Condensation

- Decarboxylation

- The Malonic Ester and Acetoacetic Ester Synthesis

- The Michael Addition Reaction and Conjugate Addition

- The Robinson Annulation

- Haloform Reaction

- The Hell–Volhard–Zelinsky Reaction

- Enols and Enolates Practice Quizzes

23 Amines

- The Amide Functional Group: Properties, Synthesis, and Nomenclature

- Basicity of Amines And pKaH

- 5 Key Basicity Trends of Amines

- The Mesomeric Effect And Aromatic Amines

- Nucleophilicity of Amines

- Alkylation of Amines (Sucks!)

- Reductive Amination

- The Gabriel Synthesis

- Some Reactions of Azides

- The Hofmann Elimination

- The Hofmann and Curtius Rearrangements

- The Cope Elimination

- Protecting Groups for Amines - Carbamates

- The Strecker Synthesis of Amino Acids

- Introduction to Peptide Synthesis

- Reactions of Diazonium Salts: Sandmeyer and Related Reactions

- Amine Practice Questions

24 Carbohydrates

- D and L Notation For Sugars

- Pyranoses and Furanoses: Ring-Chain Tautomerism In Sugars

- What is Mutarotation?

- Reducing Sugars

- The Big Damn Post Of Carbohydrate-Related Chemistry Definitions

- The Haworth Projection

- Converting a Fischer Projection To A Haworth (And Vice Versa)

- Reactions of Sugars: Glycosylation and Protection

- The Ruff Degradation and Kiliani-Fischer Synthesis

- Isoelectric Points of Amino Acids (and How To Calculate Them)

- Carbohydrates Practice

- Amino Acid Quizzes

25 Fun and Miscellaneous

- A Gallery of Some Interesting Molecules From Nature

- Screw Organic Chemistry, I'm Just Going To Write About Cats

- On Cats, Part 1: Conformations and Configurations

- On Cats, Part 2: Cat Line Diagrams

- On Cats, Part 4: Enantiocats

- On Cats, Part 6: Stereocenters

- Organic Chemistry Is Shit

- The Organic Chemistry Behind "The Pill"

- Maybe they should call them, "Formal Wins" ?

- Why Do Organic Chemists Use Kilocalories?

- The Principle of Least Effort

- Organic Chemistry GIFS - Resonance Forms

- Reproducibility In Organic Chemistry

- What Holds The Nucleus Together?

- How Reactions Are Like Music

- Organic Chemistry and the New MCAT

26 Organic Chemistry Tips and Tricks

- Common Mistakes: Formal Charges Can Mislead

- Partial Charges Give Clues About Electron Flow

- Draw The Ugly Version First

- Organic Chemistry Study Tips: Learn the Trends

- The 8 Types of Arrows In Organic Chemistry, Explained

- Top 10 Skills To Master Before An Organic Chemistry 2 Final

- Common Mistakes with Carbonyls: Carboxylic Acids... Are Acids!

- Planning Organic Synthesis With "Reaction Maps"

- Alkene Addition Pattern #1: The "Carbocation Pathway"

- Alkene Addition Pattern #2: The "Three-Membered Ring" Pathway

- Alkene Addition Pattern #3: The "Concerted" Pathway

- Number Your Carbons!

- The 4 Major Classes of Reactions in Org 1

- How (and why) electrons flow

- Grossman's Rule

- Three Exam Tips

- A 3-Step Method For Thinking Through Synthesis Problems

- Putting It Together

- Putting Diels-Alder Products in Perspective

- The Ups and Downs of Cyclohexanes

- The Most Annoying Exceptions in Org 1 (Part 1)

- The Most Annoying Exceptions in Org 1 (Part 2)

- The Marriage May Be Bad, But the Divorce Still Costs Money

- 9 Nomenclature Conventions To Know

- Nucleophile attacks Electrophile

27 Case Studies of Successful O-Chem Students

- Success Stories: How Corina Got The The "Hard" Professor - And Got An A+ Anyway

- How Helena Aced Organic Chemistry

- From a "Drop" To B+ in Org 2 – How A Hard Working Student Turned It Around

- How Serge Aced Organic Chemistry

- Success Stories: How Zach Aced Organic Chemistry 1

- Success Stories: How Kari Went From C– to B+

- How Esther Bounced Back From a "C" To Get A's In Organic Chemistry 1 And 2

- How Tyrell Got The Highest Grade In Her Organic Chemistry Course

- This Is Why Students Use Flashcards

- Success Stories: How Stu Aced Organic Chemistry

- How John Pulled Up His Organic Chemistry Exam Grades

- Success Stories: How Nathan Aced Organic Chemistry (Without It Taking Over His Life)

- How Chris Aced Org 1 and Org 2

- Interview: How Jay Got an A+ In Organic Chemistry

- How to Do Well in Organic Chemistry: One Student's Advice

- "America's Top TA" Shares His Secrets For Teaching O-Chem

- "Organic Chemistry Is Like..." - A Few Metaphors

- How To Do Well In Organic Chemistry: Advice From A Tutor

- Guest post: "I went from being afraid of tests to actually looking forward to them".

Thank you so much for this information and for taking time to research and write all of this for us!!! I agree that flashcards seem helpful (I haven’t done them before but I will next semester) to start with before going into the more conceptual topics.

Totally agree with the “Start shallow, then go deep.” I learned that the hard way!

James – did you do a breakdown of how many points these questions make up? Given that breakdown, I wouldn’t be surprised if the “provide mechanism” questions constitute almost half the points.

This is the type of place where the “instructor provides old exams” can be most useful, because it can help you figure out the types of stuff to study for. A former ChemEd grad student actually did an assessment of my exams once to get a breakdown of the types of questions I ask. I don’t remember the results, but I also think that’s evolved over time. Nowadays I write a lot more free response and essay questions to test understanding. It’s a bear to grade, but that’s what I like. I’ve also learned to expect a 50% average for simple “predict the product” problems so I don’t put too many of them on exams any more.

I think a lot of the improvement that occurs in Orgo II comes from the fact that the students understand the instructor better (typically the same instructor for both semesters). I give all my students 3 years worth of exams, so they should have a good idea of the type of stuff I like. The downside is that too many of them just study the old exams, instead of using the old exams to determine whether their preparation is adequate. Unfortunately for students, I have lots of questions in my head with different ways to present them, and so don’t end up recycling a lot of old exam material.

Thank you for sharing. Hope to hear more from you.